---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

R. 2. Examples of use (more)

Introduction Use as calculator Other calculi Figures Graphs Statistics More

This guide is just an introduction to the main commands, to get confident with the

software and to illustrate some of the activities that can be faced with it. It is

an extended version of this. At the bottom there is an index (for others see here).

# (A) At startup, the program has a line beginning with >. After this symbol I can

# type an "input", followed by "enter key", and get a possible "output", written in

# blue, preceded by [1]. With some "commands" I can have more lines of output; in

# these cases the following lines are preceded by [2], [3], ... A simple example:

> 10/4

# [1] 2.5

# In the examples we will do we will not put > so that the commands can be copied from

# here and put directly into R

# The parts that follow # (like these) are for those who read; they can be copied to R

# but do not give rise to any execution: in R the texts preceded by # are just comments.

# You can change size and style of the font, and other aspects (for example, to use the

# projector): see.

# To use many commands (indicated by point (C) down) you must first write to R (only

# once) the following line. You should copy it and paste it immediately:

source("http://macosa.dima.unige.it/r.R")

# A simple way to terminate the current session without using the mouse consists in

# typing quit()

USE as CALCULATOR

# (B) R can be used as an excellent calculator; the division is "/", the multiplication

# "*", a power elevation, such as 6 to 2, is indicated by 6^2, where "^" indicates that

# the 2 should be thought as if it was raised.

6+2

# [1] 8

6-2; 2-6; 6*2; 6/2; 6^2

# [1] 4

# [1] -4

# [1] 12

# [1] 3

# [1] 36

# As you have seen, I can run multiple commands separated by ;. I get the results

# one below the other.

# The results can have many or infinite digits; only a few are shown:

5000/12

# [1] 416.6667

# 5000/12 results 416.66666 ... but the program displays only 7 digits rounding the

# final figure: 416.66666... -> 416.6667 (it is closer to 5000/12 than 416.6666).

# (C) In addition to + * / ... with R you can calculate the values of other functions,

# which relate outputs to inputs. Generally the inputs are enclosed in brackets. Some

# examples, round, sqrt or rad2, rad3:

round(5000/12, 3); round(5000/12, 1); round(5000/12, 0); round(5000/12, -2)

# [1] 416.667

# [1] 416.7

# [1] 417

# [1] 400

# round(5000/12, 3) rounds to the 3rd digit after ".", round(5000/12, 1) to 1st digit,

# round(5000/12, 0) to integers, rounds(5000/12, -2) to hundreds. For example, if I

# have a cost of 5000 euros to divide between 12 people I calculate 5000/12, rounding

# the result to the cents, that is to the 2nd digit after ".":

round(5000/12, 2)

# [1] 416.67

sqrt(4); sqrt(3); sqrt(3)^2

# [1] 2

# [1] 1.732051

# [1] 3

# sqrt acts for "square root". The side of a square that must have the area of 3 m^2

# must be 1.73 m, ie 173 cm.

# Instead of sqrt you can use rad2. You can use rad3 to calculate the cubic root.

# The side (in cm) of a volume cube of 500 cm^3 (half liter):

rad3(500)

# [1] 7.937005

# (D) For fractional calculations and to represent finite or periodic numbers in the

# form of fractions it may be useful the command fraction (or "frazio"). Examples:

fraction(1.3333333333333); fraction(0.125); fraction(10/4); fraction(15/60+1/2)

# 4/3 1/8 5/2 3/4

# To get a ratio in percentage form, eg 23/54 as 42.6% or 43%, I do:

23/54*100; round(23/54*100,1); round(23/54*100,0)

# 42.59259 42.6 43

# To write large or small numbers you can use the so-called exponential notation, as

# you do with the calculator, using eg e3 to mean a multiplication for 10^3 and e-3 to

# mean a division for 10^3, ie a multiplication for 10^-3.

# R uses the same notation to indicate large and small numbers.

# Here are some ways to write 100 thousand and 2 tenths of a thousand:

100000; 100*1000; 100e3; 0.0002; 2e-4

# 1e+05 1e+05 1e+05 2e-04 2e-04

# If you have to calculate 15+27 and divide the result by twice the sum of 36 and 25,

# ie calculate what at school is sometimes written (12+27)/[2*(36+25)], you need to be

# careful: in math the parentheses have different meanings than those given at school:

# square brackets, [ and ],and braces, { and }, are used to indicate particular

# mathematical objects. Software, and mathematicians, write a term like the previous

# using only round parentheses: (12+27)/(2*(36+25)). They eventually change the size:

# (12+27)/(2*(36+25)). Using R you can improve readability by adding white spaces:

(12+27) / ( 2*(36+25) )

# [1] 0.3196721

# In fact, I can put all the spaces I want between brackets, numbers, and operations.

# (E) Here is how to perform the division with the rest between two integers and how

# to list the positive integers for which an integer can be divisible (its divisors).

div(13, 4)

# [1] 3 1

# 3 with remainder 1; in fact 13 = 4*3 + 1

divisors(12) # or: divisori(12)

# [1] 1 2 3 4 6 12

USE as CALCULATOR - Developments

# (E_1) Tree(1),…,Tree(18) allow you to compare how to write mathematical expressions

# on your computer on a single line, how to write them normally, and how to represent

# them with a "tree" without the use of brackets. Knowing how to switch between a

# representation and the other is important to understanding the meaning of formulas.

Trees()

#If you use Tree(1) or Tree(2) ... or Tree(18) you see expressions

#in the usual way, in "one line", as a "tree"

Tree(8)

see here

# (E_2) The results are displayed with 7 digits. If they are integer and have less

# than 13 digits they are displayed exactly:

1.23456*7.654321; 123456*7654321

# [1] 9.449719

# [1] 944971853376

# divInt(M,N,d) computes the division M by N with d decimal digits of the quotient, and

# the remainder. An example:

div(460,29)

# [1] 15 25 the integer part of the quotient and the remainder

divInt(460,29, 40)

# [1] 15 8 6 2 0 6 8 9 6 5 5 1 7 2 4 1 3 7 9 3 1 0 3 4 4 8

# [27] 2 7 5 8 6 2 0 6 8 9 6 5 5 1 7

# [1] 7

# The period of the quotient has at most N-1 digits. In this case they are exactly 28

# (the remainder is 7).

# hms(h,m,s) represents a time in various formats; hms1,hms2,hms3 give the first 3 output

hms(13,4,55); hms(13+2,4+1,55+6)

# h=: 13.08194 m: 784.9167 s: 47095 hms: 13 4 55

# h=: 15.10028 m: 906.0167 s: 54361 hms: 15 6 1

hms1(13,4,55); hms2(13,4,55); hms3(13,4,55)

# [1] 13.08194

# [1] 784.9167

# [1] 47095

Other CALCULI

# (F) In a formula like area = length*width (area of the rectangle) area, length and

# width are variables, ie the names to which values can be replaced. Also in R I can

# use variables. I have to be careful about the size of the letters: Width, WIDTH and

# width are three different variables. Example:

length = 10; width = 5

length*width

# [1] 50

length*Width

# Error: "Width" not found

# I could also put the result of length*width into another variable and then look

# for the value of it:

area = length*width

area

# [1] 50

# (G) If I have to do the same calculation referring to several numbers, such as 5, 10

# and 3, I can put these into a collection of numbers, ie put them in c(5,10,3) and

# make calculations with this new object:

c(5,10,3)*2

# [1] 10 20 6

# There are also calculations that are made specifically on the collections of objects;

# eg If I want to sort the data I put them as input of the sort function and get the

# output as data in ascending order:

sort( c(5,10,3) )

# [1] 3 5 10

# I can extract a number from a collection by pointing - between [ and ] - the place:

joe = c(5,10,3); joe[1]; joe[2]

# [1] 5

# [1] 10

# Let's see an example of use. I put in height_pupils the heights in cm of some pupils

# of a class (I use "_" to combine "height" and "pupils" in one variable, but I could

# use eg HeightPupils). Then I put them in order:

height_pupils = c(118, 135, 127, 119, 121, 124, 130, 132, 128, 122, 121, 123, 127)

sort(height_pupils)

# [1] 118 119 121 121 122 123 124 127 127 128 130 132 135

# Other calculations I can do (we see the outputs immediately):

data = height_pupils; min(data); max(data); length(data); sum(data)

# [1] 118

# [1] 135

# [1] 13

# [1] 1627

# The meaning of commands is obvious. I copied "height_pupils" into "data" so that I

# had a shorter name to write.

# NOTE If I press the arrow key "up" [^] I see the previous commands again, if I press

# the arrow key "down" [v] I see the subsequent commands: this is convenient for

# recalling or modifying them. Try to use them.

Other CALCULI - Developments

# (G_1) To assign a value to a variable, as well as =, you can use an arrow, that is

# <- or ->.

Price <- 9; 7 -> Cost; Profit = Price - Cost; Profit

# [1] 2

# Instead of min and max, I can use the command range too:

data = c(118, 135, 127, 119, 121, 124, 130, 132, 128, 122, 121, 123, 127); range(data)

# [1] 118 135

# To verify if x is in the collection Z I can use the command isin(x,Z) [what is that?

# isin=function(x,m) {n=length(m); v=FALSE; for(i in 1:n) if(x==m[i]) v=TRUE; v} see

# here for "for" ]:

isin(135,data); isin(120,data); isin("D",c("A","D",3))

# [1] TRUE [1] FALSE [1] TRUE

FIGURES

# (H) Let's see some basic commands to build geometric figures. Let's go through

# examples.

PLANE(-1,10, -1,10)

see here

# (E_2) The results are displayed with 7 digits. If they are integer and have less

# than 13 digits they are displayed exactly:

1.23456*7.654321; 123456*7654321

# [1] 9.449719

# [1] 944971853376

# divInt(M,N,d) computes the division M by N with d decimal digits of the quotient, and

# the remainder. An example:

div(460,29)

# [1] 15 25 the integer part of the quotient and the remainder

divInt(460,29, 40)

# [1] 15 8 6 2 0 6 8 9 6 5 5 1 7 2 4 1 3 7 9 3 1 0 3 4 4 8

# [27] 2 7 5 8 6 2 0 6 8 9 6 5 5 1 7

# [1] 7

# The period of the quotient has at most N-1 digits. In this case they are exactly 28

# (the remainder is 7).

# hms(h,m,s) represents a time in various formats; hms1,hms2,hms3 give the first 3 output

hms(13,4,55); hms(13+2,4+1,55+6)

# h=: 13.08194 m: 784.9167 s: 47095 hms: 13 4 55

# h=: 15.10028 m: 906.0167 s: 54361 hms: 15 6 1

hms1(13,4,55); hms2(13,4,55); hms3(13,4,55)

# [1] 13.08194

# [1] 784.9167

# [1] 47095

Other CALCULI

# (F) In a formula like area = length*width (area of the rectangle) area, length and

# width are variables, ie the names to which values can be replaced. Also in R I can

# use variables. I have to be careful about the size of the letters: Width, WIDTH and

# width are three different variables. Example:

length = 10; width = 5

length*width

# [1] 50

length*Width

# Error: "Width" not found

# I could also put the result of length*width into another variable and then look

# for the value of it:

area = length*width

area

# [1] 50

# (G) If I have to do the same calculation referring to several numbers, such as 5, 10

# and 3, I can put these into a collection of numbers, ie put them in c(5,10,3) and

# make calculations with this new object:

c(5,10,3)*2

# [1] 10 20 6

# There are also calculations that are made specifically on the collections of objects;

# eg If I want to sort the data I put them as input of the sort function and get the

# output as data in ascending order:

sort( c(5,10,3) )

# [1] 3 5 10

# I can extract a number from a collection by pointing - between [ and ] - the place:

joe = c(5,10,3); joe[1]; joe[2]

# [1] 5

# [1] 10

# Let's see an example of use. I put in height_pupils the heights in cm of some pupils

# of a class (I use "_" to combine "height" and "pupils" in one variable, but I could

# use eg HeightPupils). Then I put them in order:

height_pupils = c(118, 135, 127, 119, 121, 124, 130, 132, 128, 122, 121, 123, 127)

sort(height_pupils)

# [1] 118 119 121 121 122 123 124 127 127 128 130 132 135

# Other calculations I can do (we see the outputs immediately):

data = height_pupils; min(data); max(data); length(data); sum(data)

# [1] 118

# [1] 135

# [1] 13

# [1] 1627

# The meaning of commands is obvious. I copied "height_pupils" into "data" so that I

# had a shorter name to write.

# NOTE If I press the arrow key "up" [^] I see the previous commands again, if I press

# the arrow key "down" [v] I see the subsequent commands: this is convenient for

# recalling or modifying them. Try to use them.

Other CALCULI - Developments

# (G_1) To assign a value to a variable, as well as =, you can use an arrow, that is

# <- or ->.

Price <- 9; 7 -> Cost; Profit = Price - Cost; Profit

# [1] 2

# Instead of min and max, I can use the command range too:

data = c(118, 135, 127, 119, 121, 124, 130, 132, 128, 122, 121, 123, 127); range(data)

# [1] 118 135

# To verify if x is in the collection Z I can use the command isin(x,Z) [what is that?

# isin=function(x,m) {n=length(m); v=FALSE; for(i in 1:n) if(x==m[i]) v=TRUE; v} see

# here for "for" ]:

isin(135,data); isin(120,data); isin("D",c("A","D",3))

# [1] TRUE [1] FALSE [1] TRUE

FIGURES

# (H) Let's see some basic commands to build geometric figures. Let's go through

# examples.

PLANE(-1,10, -1,10)

# A window opens where the left figure appears: a "squared paper" with numbers that

# represent, as in a geographic map, the coordinates of the various points. The point

# whose horizontal and vertical coordinates are 7 and 4 appears red. It was plotted

# with the command:

POINT(7,4, "red")

# The smallest point (blue) was obtained with:

Point(2,4, "blue")

# By moving the mouse over the title bar of the graphics window (see below) I can move

# it. By moving over edges or angles I can resize it (see above on the right).

# A window opens where the left figure appears: a "squared paper" with numbers that

# represent, as in a geographic map, the coordinates of the various points. The point

# whose horizontal and vertical coordinates are 7 and 4 appears red. It was plotted

# with the command:

POINT(7,4, "red")

# The smallest point (blue) was obtained with:

Point(2,4, "blue")

# By moving the mouse over the title bar of the graphics window (see below) I can move

# it. By moving over edges or angles I can resize it (see above on the right).

# To delete a window I do not need, I click the red button X .

# New "planes" appear in overlapping windows. To see the old ones I can move the new

# windows.

# I can save a picture using Copy from the File menu (In Windows I can also click the

# picture, select "bitmap", then copy it in Paint, modify and save as PNG file, or in a

# word processing tool. In Mac I have to paste it directly in the tool I want to use; I

# can use an application similar to Paint, PaintBrush, which, if it is not already

# installed on your Mac, you can download for free [search on Google "paintbrush"])

# The initial window was wide and high about 3 inches. If I type BF and HF (base and

# height of the window frame) I get:

BF;HF

# [1] 3

# [1] 3

# I can change the size of the window. Example:

BF=4; HF=2; PLANE(-50,50, 0,50)

# To delete a window I do not need, I click the red button X .

# New "planes" appear in overlapping windows. To see the old ones I can move the new

# windows.

# I can save a picture using Copy from the File menu (In Windows I can also click the

# picture, select "bitmap", then copy it in Paint, modify and save as PNG file, or in a

# word processing tool. In Mac I have to paste it directly in the tool I want to use; I

# can use an application similar to Paint, PaintBrush, which, if it is not already

# installed on your Mac, you can download for free [search on Google "paintbrush"])

# The initial window was wide and high about 3 inches. If I type BF and HF (base and

# height of the window frame) I get:

BF;HF

# [1] 3

# [1] 3

# I can change the size of the window. Example:

BF=4; HF=2; PLANE(-50,50, 0,50)

# If I do not change BF and HF the size remains these. Horizontal coordinates range (at

# least) from -50 to 50. Vertical coordinates range (at least) from 0 to 50. To plot

# the new windows in the original dimensions I type:

BF=3; HF=3

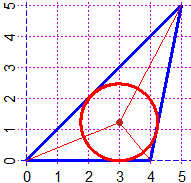

# I write 4,2 to indicate the point having the coordinates 4 and 2. With the following

# commands I draw in blue the circle whose center is 4,2 and radius is 3 and in black

# the center. Then I draw the circle that passes through the 3 points whose first

# coordinates I put in x and the second in y. I draw the circle in red and the points

# in black. Instead of "black" I can use number 1.

PLANE(-1,10, -1,10)

circle(4,2, 3, "blue"); POINT(4,2,"black")

x = c(5, 8, 9); y = c(9, 3, 7.5)

circle3p(x,y, "red"); POINT(x,y, 1)

# If I do not change BF and HF the size remains these. Horizontal coordinates range (at

# least) from -50 to 50. Vertical coordinates range (at least) from 0 to 50. To plot

# the new windows in the original dimensions I type:

BF=3; HF=3

# I write 4,2 to indicate the point having the coordinates 4 and 2. With the following

# commands I draw in blue the circle whose center is 4,2 and radius is 3 and in black

# the center. Then I draw the circle that passes through the 3 points whose first

# coordinates I put in x and the second in y. I draw the circle in red and the points

# in black. Instead of "black" I can use number 1.

PLANE(-1,10, -1,10)

circle(4,2, 3, "blue"); POINT(4,2,"black")

x = c(5, 8, 9); y = c(9, 3, 7.5)

circle3p(x,y, "red"); POINT(x,y, 1)

# The center of the red circle is also drawn. I got it and the radius as follows:

center3p; radius3p

# [1] 6.076923 5.788462

# [1] 3.387291

POINT(6.076923, 5.788462, "orange")

# Here are some color names [enter Colors() to see others]:

# The center of the red circle is also drawn. I got it and the radius as follows:

center3p; radius3p

# [1] 6.076923 5.788462

# [1] 3.387291

POINT(6.076923, 5.788462, "orange")

# Here are some color names [enter Colors() to see others]:

# 1 black 2 grey 3 white 4 brown 5 orange 6 red 7 pink

# 8 magenta 9 blue 10 cyan 11 yellow 12 green 13 seagreen

# (I) Let's see some other figure: lines, angles, ...

PLANE(0,10, 0,10)

# I plot a few points (figure on the left):

POINT(1,9,"blue"); POINT(4,9, "blue"); POINT(0,6,"brown"); POINT(4,8, "brown")

POINT(3,5,"magenta"); POINT(7,4, "magenta"); POINT(2,1, "red"); POINT(7,2,"red")

# 1 black 2 grey 3 white 4 brown 5 orange 6 red 7 pink

# 8 magenta 9 blue 10 cyan 11 yellow 12 green 13 seagreen

# (I) Let's see some other figure: lines, angles, ...

PLANE(0,10, 0,10)

# I plot a few points (figure on the left):

POINT(1,9,"blue"); POINT(4,9, "blue"); POINT(0,6,"brown"); POINT(4,8, "brown")

POINT(3,5,"magenta"); POINT(7,4, "magenta"); POINT(2,1, "red"); POINT(7,2,"red")

# then (on the right) two segments, a halfline and a straight line for two points (the

# latter are only partially traced):

segm(1,9, 4,9, "blue"); segm(0,6, 4,8, "brown")

halfline(3,5, 7,4, "magenta") # the halfline starting from 3,5, passing through 7,4

line2p(2,1, 7,2, "red") # the line passing through 2,1 and 7,2

# Let's see some other simple figure:

# then (on the right) two segments, a halfline and a straight line for two points (the

# latter are only partially traced):

segm(1,9, 4,9, "blue"); segm(0,6, 4,8, "brown")

halfline(3,5, 7,4, "magenta") # the halfline starting from 3,5, passing through 7,4

line2p(2,1, 7,2, "red") # the line passing through 2,1 and 7,2

# Let's see some other simple figure:

PLANE(0,10, 0,10)

A = c(0,6); B = c(2,10); C = c(5,4)

POINT(A[1],A[2], "blue"); POINT(B[1],B[2], "blue"); POINT(C[1],C[2], "blue")

line(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2], "blue"); line(A[1],A[2], C[1],C[2], "blue")

# I have plotted points and traced thin segments with the command line (instead of

# segm). I have stored every point (A, B, C) in a variable, as collection - see (G) -

# of his coordinates.

# With point_point I calculate the distance of A from B, with inclination the

# inclination of AB e AC. With angle I can measure the angle CAB directly.

# With SLOPE I calculate the slope of the line of a given inclination.

point_point(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2])

# [1] 4.472136

inclination(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2])

# [1] 63.43495

SLOPE(63.43495)

# [1] 2 # (B[2]-A[2])/(B[1]-A[1])

inclination(A[1],A[2], C[1],C[2])

# [1] -21.80141

angle(C,A,B)

# [1] 85.23636

# Then with mid2p I traced the middle point of AB

mid2p(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2], "red")

# In the figure on the right I traced the axis of AB, ie the line perpendicular to AB

# and passing through its middle point.

perp2p(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2], "red")

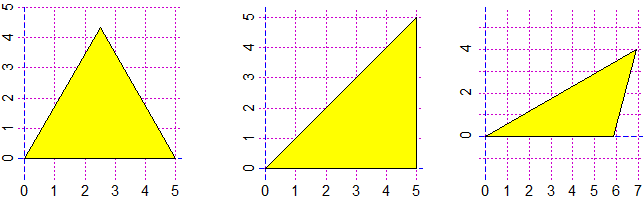

# (J) Let's see how to draw polyline and polygons. With polyline I trace the line

# formed by the segments joining the points with the indicated coordinates. In the

# following example the first point coincides with the last one (in this case the

# polyline is a polygon). leng calculates its length.

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10)

x = c(-3,2,8,8,-3); y = c(1,1,9,-1,1)

polyline(x,y, "blue"); POINT(x,y, "red")

leng(x,y)

# [1] 36.18034

# If I want to calculate the length of the first 3 segments, between 1^ and 4^ points:

leng(x[1:4],y[1:4])

# [1] 25

PLANE(0,10, 0,10)

A = c(0,6); B = c(2,10); C = c(5,4)

POINT(A[1],A[2], "blue"); POINT(B[1],B[2], "blue"); POINT(C[1],C[2], "blue")

line(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2], "blue"); line(A[1],A[2], C[1],C[2], "blue")

# I have plotted points and traced thin segments with the command line (instead of

# segm). I have stored every point (A, B, C) in a variable, as collection - see (G) -

# of his coordinates.

# With point_point I calculate the distance of A from B, with inclination the

# inclination of AB e AC. With angle I can measure the angle CAB directly.

# With SLOPE I calculate the slope of the line of a given inclination.

point_point(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2])

# [1] 4.472136

inclination(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2])

# [1] 63.43495

SLOPE(63.43495)

# [1] 2 # (B[2]-A[2])/(B[1]-A[1])

inclination(A[1],A[2], C[1],C[2])

# [1] -21.80141

angle(C,A,B)

# [1] 85.23636

# Then with mid2p I traced the middle point of AB

mid2p(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2], "red")

# In the figure on the right I traced the axis of AB, ie the line perpendicular to AB

# and passing through its middle point.

perp2p(A[1],A[2], B[1],B[2], "red")

# (J) Let's see how to draw polyline and polygons. With polyline I trace the line

# formed by the segments joining the points with the indicated coordinates. In the

# following example the first point coincides with the last one (in this case the

# polyline is a polygon). leng calculates its length.

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10)

x = c(-3,2,8,8,-3); y = c(1,1,9,-1,1)

polyline(x,y, "blue"); POINT(x,y, "red")

leng(x,y)

# [1] 36.18034

# If I want to calculate the length of the first 3 segments, between 1^ and 4^ points:

leng(x[1:4],y[1:4])

# [1] 25

# With polyC I close the polyline by coloring the polygon it delimits.

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10); polyC(x,y,"yellow")

# With polyC I can not rewrite the starting point: x=c(-3,2,8,8), y=c(1,1,9,-1)

# With color 0 the polygon is transparent

# At the yellow polygon I added a red rectangle, obtained with:

A = c(0,2, 2,0, 0); B = c(4,4, 7,7, 4); polyline(A,B, "red")

----------------------------------------------

# We shall see later how to use PPP(). It can be usefully employed by the teacher in

# the basic school to build animated documents. Two examples:

BF=4; HF=4; PLANE(-5,9,-5,9)

A = function() {PPP(); A1=round(xP); A2=round(yP);

CLEAN(-5,9,-5,9); BOX(); POINT(A1,A2,"brown");

PPP(); B1=round(xP); B2=round(yP); POINT(B1,B2,"brown");

line(A1,A2,B1,B2, "brown"); POINT( (A1+B1)/2,(A2+B2)/2,"seagreen");

cat(A1," ",A2," ",B1," ",B2, " Green point = ?","\n")}

cat("Type A() and click the screen twice. What are the coordinates of the green dot?","\n")

# Type A() and click the screen twice. What are the coordinates of the green dot?

A()

# -1 6 6 2 Green point = ?

# With polyC I close the polyline by coloring the polygon it delimits.

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10); polyC(x,y,"yellow")

# With polyC I can not rewrite the starting point: x=c(-3,2,8,8), y=c(1,1,9,-1)

# With color 0 the polygon is transparent

# At the yellow polygon I added a red rectangle, obtained with:

A = c(0,2, 2,0, 0); B = c(4,4, 7,7, 4); polyline(A,B, "red")

----------------------------------------------

# We shall see later how to use PPP(). It can be usefully employed by the teacher in

# the basic school to build animated documents. Two examples:

BF=4; HF=4; PLANE(-5,9,-5,9)

A = function() {PPP(); A1=round(xP); A2=round(yP);

CLEAN(-5,9,-5,9); BOX(); POINT(A1,A2,"brown");

PPP(); B1=round(xP); B2=round(yP); POINT(B1,B2,"brown");

line(A1,A2,B1,B2, "brown"); POINT( (A1+B1)/2,(A2+B2)/2,"seagreen");

cat(A1," ",A2," ",B1," ",B2, " Green point = ?","\n")}

cat("Type A() and click the screen twice. What are the coordinates of the green dot?","\n")

# Type A() and click the screen twice. What are the coordinates of the green dot?

A()

# -1 6 6 2 Green point = ?

BF=4; HF=4; PLANE(0,12,0,12)

S=12; X=3; Y=S/X; polyline(c(0,X,X,0,0),c(0,0,Y,Y,0), "blue"); POINT(X,Y,"red")

A = function() {PPP(); x=round(xP,1); polyline(c(0,X,X,0,0),c(0,0,Y,Y,0), "grey"); POINT(X,Y,"red");

X<<-x; Y<<-S/x; polyline(c(0,X,X,0,0),c(0,0,Y,Y,0), "blue"); POINT(X,Y,"red")}

cat("Type A() and click the screen. Then repeat several times. What do you observe?","\n")

# Type A() and click the screen. Then repeat several times. What do you observe?

A()

...

FIGURES - Developments

# (J_1) It's easy calculate the area of polygon. In the previous case:

x = c(-3,2,8,8); y = c(1,1,9,-1)

areaPol(x,y)

# [1] 35

See here to calculate the area of Italy.

See here to calculare the area under the graph of a function.

# The value of π ("pi"), ie the area of a circle of radius 1, and the length of a

# semicircle of radius 1 (it is rounded with 7 digits):

pi

# [1] 3.141593

BF=4; HF=4; PLANE(0,12,0,12)

S=12; X=3; Y=S/X; polyline(c(0,X,X,0,0),c(0,0,Y,Y,0), "blue"); POINT(X,Y,"red")

A = function() {PPP(); x=round(xP,1); polyline(c(0,X,X,0,0),c(0,0,Y,Y,0), "grey"); POINT(X,Y,"red");

X<<-x; Y<<-S/x; polyline(c(0,X,X,0,0),c(0,0,Y,Y,0), "blue"); POINT(X,Y,"red")}

cat("Type A() and click the screen. Then repeat several times. What do you observe?","\n")

# Type A() and click the screen. Then repeat several times. What do you observe?

A()

...

FIGURES - Developments

# (J_1) It's easy calculate the area of polygon. In the previous case:

x = c(-3,2,8,8); y = c(1,1,9,-1)

areaPol(x,y)

# [1] 35

See here to calculate the area of Italy.

See here to calculare the area under the graph of a function.

# The value of π ("pi"), ie the area of a circle of radius 1, and the length of a

# semicircle of radius 1 (it is rounded with 7 digits):

pi

# [1] 3.141593

# The square all of whose sides are tangents to this circle has area 2·2 = 4

# If the radius is 2, 3, … area and semicircunference of the circle are π·4, π·9, …

# and π·2, π·3, …

# (J_2) I can print the coordinates of any point of the screen. If I type:

PLANE(-3,6,-4,5)

xy(2)

# and click the point marked with a cross (see below), I obtain:

# [1] 4.7 1.3

# They are rounded to 2 digits. If I want to round to 3 digits I type xy(3)

# (J_3) With arrow and dart you can draw arrows. With dirArrow you obtains direction

# and length. See below and the following commands:

# The square all of whose sides are tangents to this circle has area 2·2 = 4

# If the radius is 2, 3, … area and semicircunference of the circle are π·4, π·9, …

# and π·2, π·3, …

# (J_2) I can print the coordinates of any point of the screen. If I type:

PLANE(-3,6,-4,5)

xy(2)

# and click the point marked with a cross (see below), I obtain:

# [1] 4.7 1.3

# They are rounded to 2 digits. If I want to round to 3 digits I type xy(3)

# (J_3) With arrow and dart you can draw arrows. With dirArrow you obtains direction

# and length. See below and the following commands:

arrow(-2,3, 2,5, "red"); arrow(2,5, 4,4, "red")

dart(-2,2, 2,4, "black"); dart(2,4, 4,3, "black")

dirArrow(-2,2, 2,4)

# dir. = 26.56505° leng. = 4.472136

dirArrow1(-2,2, 2,4); dirArrow2(-2,2, 2,4)

# [1] 26.56505 [1] 4.472136

# With Arrow and Dart instead of the 2nd point I can put direction and length:

Arrow(-2,1, 26.56505, 4.472136, "blue")

Dart(-2,0, 26.56505, 4.472136, "seagreen")

# Arrowx and Arrowy give the point of the arrow:

Arrowx(-2,0, 26.56505, 4.472136); Arrowy(-2,0, 26.56505, 4.472136)

# [1] 2 [1] 2

# With Direction and Directio the point of the arrow is not drawn:

Direction(0,-3, 0,4, "brown"); Direction(0,-3, 60,4, "orange")

Directio(0,-3, 30,4, "black")

Directionx; Directiony; POINT(Directionx, Directiony, "blue")

# [1] 3.464102 [1] -1

# In substance, Direction(a,b, D, R, col) draws a radius width center in (a,b),

# direction D and lenght R

# With arroW and ArroW I have an intermediate thickness between "dart" and "arrow".

# (J_4) line_line(x,y, p,q, a,b, u,v) is the intersection of the line through x,y and

# p,q and the line through a,b and u,v. The coordinates of it are in solut[1],solut[2].

# See below, on the left:

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10)

POINT(8,-1, 1); POINT(4,10, 1); line2p(8,-1, 4,10, "seagreen")

POINT(2,-1, 1); POINT(8,7, 1); POINT(2,1, 1); POINT(8,9, 1)

# We remember that instead of "black" we can use 1

line2p(2,-1, 8,7, "brown"); line2p(2,1, 8,9, "blue")

line_line(2,-1, 8,7, 2,1, 8,9)

# [1] "rette parallele/parallel lines"

line_line(8,-1, 4,10, 2,1, 8,9)

# [1] 5.551020 5.734694

POINT(solut[1],solut[2],"red")

arrow(-2,3, 2,5, "red"); arrow(2,5, 4,4, "red")

dart(-2,2, 2,4, "black"); dart(2,4, 4,3, "black")

dirArrow(-2,2, 2,4)

# dir. = 26.56505° leng. = 4.472136

dirArrow1(-2,2, 2,4); dirArrow2(-2,2, 2,4)

# [1] 26.56505 [1] 4.472136

# With Arrow and Dart instead of the 2nd point I can put direction and length:

Arrow(-2,1, 26.56505, 4.472136, "blue")

Dart(-2,0, 26.56505, 4.472136, "seagreen")

# Arrowx and Arrowy give the point of the arrow:

Arrowx(-2,0, 26.56505, 4.472136); Arrowy(-2,0, 26.56505, 4.472136)

# [1] 2 [1] 2

# With Direction and Directio the point of the arrow is not drawn:

Direction(0,-3, 0,4, "brown"); Direction(0,-3, 60,4, "orange")

Directio(0,-3, 30,4, "black")

Directionx; Directiony; POINT(Directionx, Directiony, "blue")

# [1] 3.464102 [1] -1

# In substance, Direction(a,b, D, R, col) draws a radius width center in (a,b),

# direction D and lenght R

# With arroW and ArroW I have an intermediate thickness between "dart" and "arrow".

# (J_4) line_line(x,y, p,q, a,b, u,v) is the intersection of the line through x,y and

# p,q and the line through a,b and u,v. The coordinates of it are in solut[1],solut[2].

# See below, on the left:

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10)

POINT(8,-1, 1); POINT(4,10, 1); line2p(8,-1, 4,10, "seagreen")

POINT(2,-1, 1); POINT(8,7, 1); POINT(2,1, 1); POINT(8,9, 1)

# We remember that instead of "black" we can use 1

line2p(2,-1, 8,7, "brown"); line2p(2,1, 8,9, "blue")

line_line(2,-1, 8,7, 2,1, 8,9)

# [1] "rette parallele/parallel lines"

line_line(8,-1, 4,10, 2,1, 8,9)

# [1] 5.551020 5.734694

POINT(solut[1],solut[2],"red")

# point_inclina(x,y, d, col) draws the line through x,y with the direction of d degrees

# whereas point_incl draws a thin line.

# line_line2(x,y, d1, a,b, d2) is the intersection of the line through x,y with

# direction d1 and the line through a,b and direction d2. The coordinates of it are in

# solut[1],solut[2]. point_line(x,y, a,b,u,v) is the distance between the point x,y

# and the line through a,b and u,v. point_line2(x,y, a,b,u,v) supplies the coordinates

# of the closest point by x,y of the line.

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10)

POINT(-1,5, 1); point_inclina(-1,5, 80, "magenta"); point_incl(-1,5, -30, 1)

POINT(6,5, "blue"); point_incl(6,5, 20, "blue")

line_line2(-1,5, 80, 6,5, 20)

# [1] -1.480053 2.277483

POINT(solut[1],solut[2], "brown")

point_line(6,5, solut[1],solut[2], -1,5)

# [1] 6.893654

point_line2(6,5, solut[1],solut[2], -1,5)

# [1] -0.7889242 6.1970705

POINT(solut[1],solut[2], "seagreen")

line(solut[1],solut[2], 6,5, "red")

# If you use noPrint=1 before line_line or line_line2 the value is not printed (they

# are in solut).

# Another picture:

# point_inclina(x,y, d, col) draws the line through x,y with the direction of d degrees

# whereas point_incl draws a thin line.

# line_line2(x,y, d1, a,b, d2) is the intersection of the line through x,y with

# direction d1 and the line through a,b and direction d2. The coordinates of it are in

# solut[1],solut[2]. point_line(x,y, a,b,u,v) is the distance between the point x,y

# and the line through a,b and u,v. point_line2(x,y, a,b,u,v) supplies the coordinates

# of the closest point by x,y of the line.

PLANE(-3,9,-2,10)

POINT(-1,5, 1); point_inclina(-1,5, 80, "magenta"); point_incl(-1,5, -30, 1)

POINT(6,5, "blue"); point_incl(6,5, 20, "blue")

line_line2(-1,5, 80, 6,5, 20)

# [1] -1.480053 2.277483

POINT(solut[1],solut[2], "brown")

point_line(6,5, solut[1],solut[2], -1,5)

# [1] 6.893654

point_line2(6,5, solut[1],solut[2], -1,5)

# [1] -0.7889242 6.1970705

POINT(solut[1],solut[2], "seagreen")

line(solut[1],solut[2], 6,5, "red")

# If you use noPrint=1 before line_line or line_line2 the value is not printed (they

# are in solut).

# Another picture:

# While perp2p traces the axis of a segment, perp3p(A,B,C,D, H,K, col) traces the segment

# perpendicular to the line passing through (A,B) and (C,D) that starts from (H,K).

PLANE(-3,9,-1,11)

POINT(-1,2,"brown"); POINT(7,9,"brown")

line(-1,2, 7,9, "brown")

POINT(8,3, "seagreen")

noPrint=1; perp3p(-1,2, 7,9, 8,3, "seagreen")

POINT(solut[1],solut[2],"red")

# If I don't use "noPrint" I also get the coordinates of the "red" point:

# [1] 4.592920 6.893805

# symm(H,K, A,B,C,D) gives the point symmetric to (H,K) with respect to the line

# passing through (A,B) and (C,D) (the blue point is symmetric to the green point)

Q = symm(8,3, -1,2,7,9); Q

# [1] 1.185841 10.787611

POINT(Q[1],Q[2], "blue")

# symm2(H,K, A,B,d) gives the point symmetric to (H,K) with respect to the line passing

# through (A,B) with the direction of d degrees. Here's how to get the same point:

d = inclination(-1,2, 7,9); d

# [1] 41.18593

U = symm2(8,3, 7,9, d); POINT(U[1],U[2],"blue")

# If you want to draw the tangent line to a circle with center C at a point P you can

# use the command tan_circle(C1,C2, P1,P2, col): see the figure above on the right.

# (if I know that C in 8,3 and that P is 4.592920,6.893805)

BF=3; HF=3

PLANE(-3,9,-1,11)

POINT(8,3, "seagreen")

P = c(4.592920, 6.893805)

POINT(P[1],P[2], "red")

# the circle with center 8,3 e radius equal to the distance between 8,3 and T

circle(8,3, point_point(8,3, P[1],P[2]), "red")

tan_circle(8,3, P[1],P[2], "blue")

# tan_circl draws a thin line

# For the inclination of CP / the radius you can use "inclination" / "point_point". For

# the tangent lines to a circle from a point see the command P_tan. If you know the

# radius R (= CP), to trace P you can also use (see ↓) circleA(8,3, R, 41.18593,"red")

# (J_5) I can easily plot a point on a circle giving the angle that expresses the

# direction in which it is reachable from the center. With circleA(x,y, r, D, col) I

# plot the point of the circle with center x,y and radius r in the direction D. With

# circleA2(x,y, r, D) I print the coordinates. See the picture on the left.

# I can use also xrot(D) and yrot(D), which give the coordinates of the point of the

# circle with center 0,0 and radius 1 in the direction D.

PLANE(-4,7, -3,8)

circle(0,4, 3, "blue")

circleA(0,4, 3, 45, "orange"); circleA2(0,4, 3, 45)

# [1] 2.12132 6.12132

ang=c(120,240); circleA(0,4, 3, ang, "red")

0+xrot(45)*3; 4+yrot(45)*3 # as: circleA2(0,4, 3, 45)[1]; circleA2(0,4, 3, 45)[2]

# [1] 2.12132 [1] 6.12132

# If the circle is specified with 3 points I use the commands circle3pA and circle3pA2:

x=c(2,4,7); y=c(-2,-3,1); POINT(x,y,"black")

circle3p(x,y, "red")

ang=c(90,180,-45); circle3pA(x,y, ang, "blue")

circle3pA2(x,y, ang)

# [1] 4.22727273 1.26399891 6.32262374 2.91781928 -0.04545455 -2.14080556

type(4.6,3.7,"P"); type(0.5,-0.6,"Q")

# I wrote the word "P" and "Q" on the picture with the command type.

# The names (as P, Q, blue) are written between double quotes (") or simple quotes (').

# While perp2p traces the axis of a segment, perp3p(A,B,C,D, H,K, col) traces the segment

# perpendicular to the line passing through (A,B) and (C,D) that starts from (H,K).

PLANE(-3,9,-1,11)

POINT(-1,2,"brown"); POINT(7,9,"brown")

line(-1,2, 7,9, "brown")

POINT(8,3, "seagreen")

noPrint=1; perp3p(-1,2, 7,9, 8,3, "seagreen")

POINT(solut[1],solut[2],"red")

# If I don't use "noPrint" I also get the coordinates of the "red" point:

# [1] 4.592920 6.893805

# symm(H,K, A,B,C,D) gives the point symmetric to (H,K) with respect to the line

# passing through (A,B) and (C,D) (the blue point is symmetric to the green point)

Q = symm(8,3, -1,2,7,9); Q

# [1] 1.185841 10.787611

POINT(Q[1],Q[2], "blue")

# symm2(H,K, A,B,d) gives the point symmetric to (H,K) with respect to the line passing

# through (A,B) with the direction of d degrees. Here's how to get the same point:

d = inclination(-1,2, 7,9); d

# [1] 41.18593

U = symm2(8,3, 7,9, d); POINT(U[1],U[2],"blue")

# If you want to draw the tangent line to a circle with center C at a point P you can

# use the command tan_circle(C1,C2, P1,P2, col): see the figure above on the right.

# (if I know that C in 8,3 and that P is 4.592920,6.893805)

BF=3; HF=3

PLANE(-3,9,-1,11)

POINT(8,3, "seagreen")

P = c(4.592920, 6.893805)

POINT(P[1],P[2], "red")

# the circle with center 8,3 e radius equal to the distance between 8,3 and T

circle(8,3, point_point(8,3, P[1],P[2]), "red")

tan_circle(8,3, P[1],P[2], "blue")

# tan_circl draws a thin line

# For the inclination of CP / the radius you can use "inclination" / "point_point". For

# the tangent lines to a circle from a point see the command P_tan. If you know the

# radius R (= CP), to trace P you can also use (see ↓) circleA(8,3, R, 41.18593,"red")

# (J_5) I can easily plot a point on a circle giving the angle that expresses the

# direction in which it is reachable from the center. With circleA(x,y, r, D, col) I

# plot the point of the circle with center x,y and radius r in the direction D. With

# circleA2(x,y, r, D) I print the coordinates. See the picture on the left.

# I can use also xrot(D) and yrot(D), which give the coordinates of the point of the

# circle with center 0,0 and radius 1 in the direction D.

PLANE(-4,7, -3,8)

circle(0,4, 3, "blue")

circleA(0,4, 3, 45, "orange"); circleA2(0,4, 3, 45)

# [1] 2.12132 6.12132

ang=c(120,240); circleA(0,4, 3, ang, "red")

0+xrot(45)*3; 4+yrot(45)*3 # as: circleA2(0,4, 3, 45)[1]; circleA2(0,4, 3, 45)[2]

# [1] 2.12132 [1] 6.12132

# If the circle is specified with 3 points I use the commands circle3pA and circle3pA2:

x=c(2,4,7); y=c(-2,-3,1); POINT(x,y,"black")

circle3p(x,y, "red")

ang=c(90,180,-45); circle3pA(x,y, ang, "blue")

circle3pA2(x,y, ang)

# [1] 4.22727273 1.26399891 6.32262374 2.91781928 -0.04545455 -2.14080556

type(4.6,3.7,"P"); type(0.5,-0.6,"Q")

# I wrote the word "P" and "Q" on the picture with the command type.

# The names (as P, Q, blue) are written between double quotes (") or simple quotes (').

# circle_circle(x,y,r1, a,b,r2) finds the eventual intersections between the circle

# with center x,y and radius r1 and the circle with center a,b and radius r2. The

# figure in the center is obtained with:

PLANE(-4,7, -3,8)

circle(0,4, 3, "brown"); circle(0,-1, 2, "red")

circle_circle(0,4,3, 0,-1,2)

# [1] 0 1

P=circle_circle(0,4,3, 0,-1,2); POINT(P[1],P[2], "blue")

circle(4,-1, 1.5,"seagreen"); circle_circle(0,4,3, 4,-1,1.5)

# [1] "troppo distanti/too distant"

circle(4,6, 2,"blue"); circle_circle(0,4,3, 4,6,2)

# [1] 2.012660 6.224679 2.987340 4.275321

Q=circle_circle(0,4,3, 4,6,2); Q[1];Q[2];Q[3];Q[4]

# [1] 2.01266 [1] 6.224679 [1] 2.98734 [1] 4.275321

# To get the figure above on the right we use the commands polylineR(a,b, R,N, D, col)

# and polyRC(a,b, R,N, D, col). The first one draws the regular polygon with center

# a,b, radius R, N sides and one vertex in the direction D; the sides have the colour

# col. The second one cause the interior have the colour col. polyR draws thin sides.

PLANE(-1,5, -2,4)

POINT(2,1, "blue"); circle(2,1, 3, "red")

polylineR(2,1, 3, 5, 90, "blue"); polyR(2,1, 2, 5,90, "brown")

polyRC(4,3, 1, 4, 0, "orange")

# circle_circle(x,y,r1, a,b,r2) finds the eventual intersections between the circle

# with center x,y and radius r1 and the circle with center a,b and radius r2. The

# figure in the center is obtained with:

PLANE(-4,7, -3,8)

circle(0,4, 3, "brown"); circle(0,-1, 2, "red")

circle_circle(0,4,3, 0,-1,2)

# [1] 0 1

P=circle_circle(0,4,3, 0,-1,2); POINT(P[1],P[2], "blue")

circle(4,-1, 1.5,"seagreen"); circle_circle(0,4,3, 4,-1,1.5)

# [1] "troppo distanti/too distant"

circle(4,6, 2,"blue"); circle_circle(0,4,3, 4,6,2)

# [1] 2.012660 6.224679 2.987340 4.275321

Q=circle_circle(0,4,3, 4,6,2); Q[1];Q[2];Q[3];Q[4]

# [1] 2.01266 [1] 6.224679 [1] 2.98734 [1] 4.275321

# To get the figure above on the right we use the commands polylineR(a,b, R,N, D, col)

# and polyRC(a,b, R,N, D, col). The first one draws the regular polygon with center

# a,b, radius R, N sides and one vertex in the direction D; the sides have the colour

# col. The second one cause the interior have the colour col. polyR draws thin sides.

PLANE(-1,5, -2,4)

POINT(2,1, "blue"); circle(2,1, 3, "red")

polylineR(2,1, 3, 5, 90, "blue"); polyR(2,1, 2, 5,90, "brown")

polyRC(4,3, 1, 4, 0, "orange")

# See here how we can trace a rhombus, if we know the center

# and the directions of the diagonals

|  |

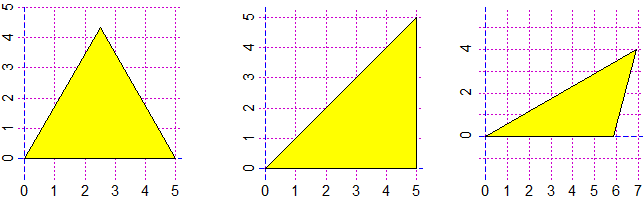

# (J_6) With ruler, goniometer and compass I can build a triangle if I know the three

# sides or two sides and the inclusive angle or two angles and the inclusive side. Here

# I can build it using triSSS, triSAS and triASA commands. With SIDES and ANGELS I have

# the measurements of sides and angles opposite them, with TRIANGLE() I have the image.

triSSS(5,5,5)

SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] 5 5 5 [1] 60 60 60

triSAS(5,90,5)

SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] 5.000000 5.000000 7.071068 [1] 45 45 90

triASA(30,8,45)

SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] 5.856406 4.141105 8.000000 [1] 45 30 105

# You can use also triASS (1 angle and the next 2 sides) that can produce two outcomes:

triASS(30,2,1); SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] 2.000000 1.000000 1.732051

# [1] 90 30 60

triASS(30,2,1.5); SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] "Then use triASS2(...) too"

# [1] 2.000000 1.500000 2.850085

# [1] 41.81031 30.00000 108.18969

triASS2(30,2,1.5); SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

[1] 2.0000000 1.5000000 0.6140168

[1] 138.18969 30.00000 11.81031

ANGLES[1]+ANGLES[3]

[1] 150

# You can use also triASS (1 angle and the next 2 sides) that can produce two outcomes:

triASS(30,2,1); SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] 2.000000 1.000000 1.732051

# [1] 90 30 60

triASS(30,2,1.5); SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

# [1] "Then use triASS2(...) too"

# [1] 2.000000 1.500000 2.850085

# [1] 41.81031 30.00000 108.18969

triASS2(30,2,1.5); SIDES; ANGLES; TRIANGLE()

[1] 2.0000000 1.5000000 0.6140168

[1] 138.18969 30.00000 11.81031

ANGLES[1]+ANGLES[3]

[1] 150

# If you want to change the size of the window in advance, first use commands BFt=...

# and HFt=...

# If you know the sides of a triangle you can use AREAT to find the area

AREAT(3,4,5); AREAT(3,4,6); AREAT(3,4,7)

# 6 5.332682 0

# Area of the first triangle above:

triASS(30,2,1); AREAT(SIDES[1],SIDES[2],SIDES[3])

# 0.8660254

# If you want to change the size of the window in advance, first use commands BFt=...

# and HFt=...

# If you know the sides of a triangle you can use AREAT to find the area

AREAT(3,4,5); AREAT(3,4,6); AREAT(3,4,7)

# 6 5.332682 0

# Area of the first triangle above:

triASS(30,2,1); AREAT(SIDES[1],SIDES[2],SIDES[3])

# 0.8660254

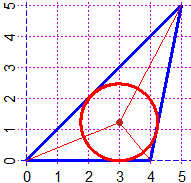

# The incentre command lets you easily trace the center

# of the circle inscribed in a triangle (the incentre

# of the triangle). An example:

PLANE(0,5, 0,5); x=c(0,4,5,0); y=c(0,0,5,0)

C = incentre(x,y); polyline(x,y,"blue")

POINT(C[1],C[2],"brown")

circle(C[1],C[2], C[2], "red")

line(0,0,C[1],C[2],"red")

line(4,0,C[1],C[2],"red")

line(5,5,C[1],C[2],"red")

# The incentre is the intersection of the bisectors: |

|

A = angle(c(4,0),c(0,0),c(5,5)); Directio(0,0, A/2, 10, "brown")

# I get a line that crosses the incentre, and (0,0)

B = angle(c(5,5),c(4,0),c(0,0)); B

# 101.3099 The angle B, and the direction from B to C:

BC = dirArrow1(4,0, 5,5); BC

# 78.69007 The line that crosses the incentre and (4,0)

Directio(4,0, BC+B/2, 10, "brown") |

|

# How to determine the tangent lines to a circle (of centre

# C1,C2 and radius R) from a point (P1,P2) with the command

# P_tan(P1,P2, C1,C2,R):

PLANE(0,6, 0,6)

POINT(5,5, "blue")

circle(3,2, 1.5, "red")

Q = P_tan(5,5, 3,2,1.5); Q

# 2.211213 3.275858 4.481095 1.762603

l2p(5,5, Q[1],Q[2], "blue")

l2p(5,5, Q[3],Q[4], "blue")

# l2p draw thinner lines than line2p |  |

# If you type CURVES(1), CURVES(2), CURVES(3) you can see

# the construction of 3 curves. If you type CURVES(1.05),

# CURVES(2.05), CURVES(3.05) the animations are faster, if

# you type CURVES(1.2), …, CURVES(1.9), …, CURVES(3.2), …,

# CURVES(3.9) the animations are slower.

# What curves are they? (see here) |

|

# See here for a more complex figure (equidistant points from three lines)

# 3 circles of different sizes and

# without points in common.

# For each pair of circles I draw

# the two common tangents and

# consider their point of

# intersection.

# The three points lie on the same

# line!

# See here. |

|

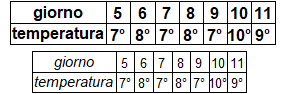

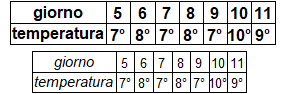

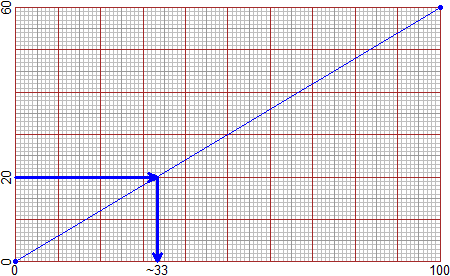

GRAPHS

# (K) Let's see how to make a graph of a phenomenon that varies with another. Plane

# (with only one uppercase letter, "P") represents the "x" and "y" with scales that

# can be different.

# Example: average consumption of kg of fresh fruit per year by an Italian.

year = c(1880,1890,1900,1910,1920,1930,1940,1950,1960,1970,1980)

fruit = c(19, 21, 23, 28, 31, 27, 23, 37, 65, 88, 79)

# max is useful for choosing the "Plane": I find the maximum is 88, so I change y

# between 0 and 90

max(fruit)

# [1] 88

BF=4; HF=2.5

Plane(1880,1980, 0,90)

polyline(year,fruit, "blue"); POINT(year,fruit,"brown")

# I also put two inscriptions along the axes with these commands:

abovex("year"); abovey("fruit")

# See here for data entry in tabular form.

# I can also graph the functions in which "x" and "y" are linked by a formula

# Ex: the conversion of the temperature in degrees Celsius to that in Fahrenheit.

# I also put two inscriptions along the axes with these commands:

abovex("year"); abovey("fruit")

# See here for data entry in tabular form.

# I can also graph the functions in which "x" and "y" are linked by a formula

# Ex: the conversion of the temperature in degrees Celsius to that in Fahrenheit.

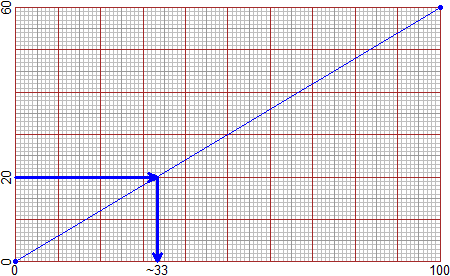

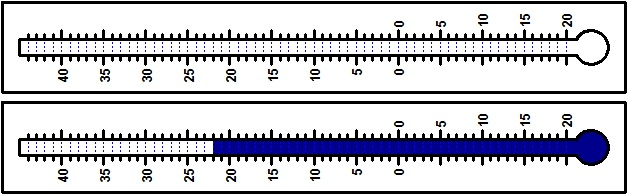

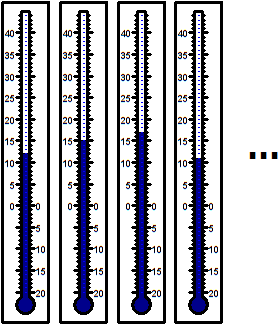

Fa = function(Ce) 32 + 72/40*Ce

Fa(-30); Fa(110)

# -22 230

Plane(-30,110, -22,230)

graph(Fa, -30,110, "brown")

abovey("°F"); abovex("°C")

POINT(100,Fa(100),"blue"); POINT(0,Fa(0),"blue")

# I got the chart on top left.

Fa(100)

# [1] 212

# To find the temperature in °F that corresponds to 100°C I simply calculated Fa(100).

# To find what is the temperature k in °C that corresponds to 100°F (see the graph on

# the right) I have to solve the problem: "for which k Fa(k) = 100?". I could do it

# "by hand". Or I can proceed using the solution command as follows:

solution(Fa,100, 20,60)

# [1] 37.77778

# I put Fa,100 because I must find the solution of the problem:

# for what input Fa is worth 100?

# I put 20,60 to indicate two values among which is the solution, derived from the

# graph. 37.777… is therefore the value of k.

# I can proceed in the same way for any other value.

# The computer does nothing but speed up a process that I could do directly with zoom,

# to find more precisely the °C degrees to which it corresponds to 100°F

Fa = function(Ce) 32 + 72/40*Ce

Fa(-30); Fa(110)

# -22 230

Plane(-30,110, -22,230)

graph(Fa, -30,110, "brown")

abovey("°F"); abovex("°C")

POINT(100,Fa(100),"blue"); POINT(0,Fa(0),"blue")

# I got the chart on top left.

Fa(100)

# [1] 212

# To find the temperature in °F that corresponds to 100°C I simply calculated Fa(100).

# To find what is the temperature k in °C that corresponds to 100°F (see the graph on

# the right) I have to solve the problem: "for which k Fa(k) = 100?". I could do it

# "by hand". Or I can proceed using the solution command as follows:

solution(Fa,100, 20,60)

# [1] 37.77778

# I put Fa,100 because I must find the solution of the problem:

# for what input Fa is worth 100?

# I put 20,60 to indicate two values among which is the solution, derived from the

# graph. 37.777… is therefore the value of k.

# I can proceed in the same way for any other value.

# The computer does nothing but speed up a process that I could do directly with zoom,

# to find more precisely the °C degrees to which it corresponds to 100°F

# If you want to see how the solutions are automatically searched, click here.

# NOTE. In more complicated situations I have to look for the solutions graphically

# before using "solution": see K_3.

# You should not use the lowercase letter c and the uppercase letter D as a function

# name; c is used for collections of objects, D for special functions (the derivatives);

# if you use these ones you can restore the original meaning by removing the new uses

# with rm("c") or rm("D").

GRAPHS - Developments

# (K_1) If you want shut down all open graphics devices (without doing it one by one:

# see) type:

graphics.off()

# Instead of graph you can use graphF(g, a,b, col) that (automatically) traces the

# graph of the function g between a and b in the colour col in a suitable window.

# If I refer to the foregoing function Fa:

graphF(Fa, -35,105, "blue")

POINT(0,Fa(0),"red"); POINT(100,Fa(100),"red")

# If I use the color 0 line and graphs are dashed. I can change the color width coldash

coldash = "red"

segm(100,0, 100,Fa(100), 0); segm(0,Fa(100), 100,Fa(100), 0)

type(-10,220,"F"); type(105,-15,"C")

line(-40,100, 110,100, 0)

x=solution(Fa,100, -40,110); POINT(x,100, "brown")

coldash = "brown"; segm(x,0, x, 100, 0); type(x,-20, 37.8)

# If you want to see how the solutions are automatically searched, click here.

# NOTE. In more complicated situations I have to look for the solutions graphically

# before using "solution": see K_3.

# You should not use the lowercase letter c and the uppercase letter D as a function

# name; c is used for collections of objects, D for special functions (the derivatives);

# if you use these ones you can restore the original meaning by removing the new uses

# with rm("c") or rm("D").

GRAPHS - Developments

# (K_1) If you want shut down all open graphics devices (without doing it one by one:

# see) type:

graphics.off()

# Instead of graph you can use graphF(g, a,b, col) that (automatically) traces the

# graph of the function g between a and b in the colour col in a suitable window.

# If I refer to the foregoing function Fa:

graphF(Fa, -35,105, "blue")

POINT(0,Fa(0),"red"); POINT(100,Fa(100),"red")

# If I use the color 0 line and graphs are dashed. I can change the color width coldash

coldash = "red"

segm(100,0, 100,Fa(100), 0); segm(0,Fa(100), 100,Fa(100), 0)

type(-10,220,"F"); type(105,-15,"C")

line(-40,100, 110,100, 0)

x=solution(Fa,100, -40,110); POINT(x,100, "brown")

coldash = "brown"; segm(x,0, x, 100, 0); type(x,-20, 37.8)

# The graph on the right is obtained with:

PLANE(-3,3, -1,5)

f1 = function(x) x^2; f2 = function(x) sqrt(x); f3 = function(x) x

graph(f1, -3,3, "black"); graph(f2, -3,3, "seagreen")

# Between -3 and 0 the graph of f2 is not drawn

coldash="red"; graph(f3, -3,3, 0)

# (K_2) The program automatically traces the graph of a function for a large number of

# points. I can trace it for a fixed number of points, if I put it in NpF.

g = function(N) N*3; NpF = 6; graphF(g, 0,5, "brown")

# The graph on the right is obtained with:

PLANE(-3,3, -1,5)

f1 = function(x) x^2; f2 = function(x) sqrt(x); f3 = function(x) x

graph(f1, -3,3, "black"); graph(f2, -3,3, "seagreen")

# Between -3 and 0 the graph of f2 is not drawn

coldash="red"; graph(f3, -3,3, 0)

# (K_2) The program automatically traces the graph of a function for a large number of

# points. I can trace it for a fixed number of points, if I put it in NpF.

g = function(N) N*3; NpF = 6; graphF(g, 0,5, "brown")

# In the center, the graph whether as a collection of 6 points or a continuous line:

graphF(g, -1,6, "yellow"); NpF = 6; graph(g, 0,5, "red")

# On the right, with NPF 6 small rings have been added.

NPF = 6; graph(g, 0,5, "black")

# If I use NpsF the segments joining x-axis are added

# In the center, the graph whether as a collection of 6 points or a continuous line:

graphF(g, -1,6, "yellow"); NpF = 6; graph(g, 0,5, "red")

# On the right, with NPF 6 small rings have been added.

NPF = 6; graph(g, 0,5, "black")

# If I use NpsF the segments joining x-axis are added

NpsF = 4; graphF(g, -1,5, "blue"); NpsF = 3; graph(g, 0,4, "red")

# (K_3) How to find the points where the graph of a function has a bump? We use the

# command maxmin (or minmax) giving the name of the function and an interval where it

# has a bumb as input:

V = function(x) (x-1/3)^2-1; graphF(V, -4,4, "red")

maxmin(V, -2,2)

# [1] 0.3333333

V( maxmin(V,-2,2) )

# [1] -1

POINT(1/3,-1, "blue") # The figure on the left:

NpsF = 4; graphF(g, -1,5, "blue"); NpsF = 3; graph(g, 0,4, "red")

# (K_3) How to find the points where the graph of a function has a bump? We use the

# command maxmin (or minmax) giving the name of the function and an interval where it

# has a bumb as input:

V = function(x) (x-1/3)^2-1; graphF(V, -4,4, "red")

maxmin(V, -2,2)

# [1] 0.3333333

V( maxmin(V,-2,2) )

# [1] -1

POINT(1/3,-1, "blue") # The figure on the left:

# If you want to see how the bump is automatically searched (and how the equations are

# solved) , click here.

# We have already seen (K) how to solve an equation. Another example:

# solve (x-1/3)^2-1 = 5 (ie V(x) = 5) for x.

# I see on the graph that the solution is between 2 and 4.

coldash="red"; segm(-4,5, 4,5, 0)

solution(V, 5, 2,4)

# [1] 2.782823

POINT( solution(V,5, 2,4), 5, "black")

# In this case (if we are able) we can solve the equation "by hand":

# (x-1/3)^2-1 = 5 I shift -1 to the right (subtraction -> addition)

# (x-1/3)^2 = 5+1 I make calculations

# (x-1/3)^2 = 6 The inverse of "^2" is the square root function

# x-1/3 = √6 I move -1/3 to the right

# x = √6+1/3 I make calculations (ie with computer)

# x = 2.782823

# If the solution of the equation corresponds to a point where the graph reaches a

# maximum or a minimum, as in the following case, the maxmin command seen above must

# be used to find the solution. Example: 28*x-99*x^2+14*x^3-49*x^4 = 2

# I look for x such that -28*x-99*x^2+14*x^3-49*x^4-2 = 0.

T = function(x) -28*x-99*x^2+14*x^3-49*x^4-2

graphF(T, -5,5, "blue")

graphF(T, -1,1, "blue")

# The graph does not climb over the x-axis. I cannot use "solution".

maxmin(T,-1,1)

# [1] 0.1428571

fraction( maxmin(T,-1,1) )

# [1] 1/7

T( 1/7 )

# [1] 1.94289e-16

# Because of the approximations, I do not obtain exactly 0.

POINT(1/7, 0, "red")

# If you want to see how the bump is automatically searched (and how the equations are

# solved) , click here.

# We have already seen (K) how to solve an equation. Another example:

# solve (x-1/3)^2-1 = 5 (ie V(x) = 5) for x.

# I see on the graph that the solution is between 2 and 4.

coldash="red"; segm(-4,5, 4,5, 0)

solution(V, 5, 2,4)

# [1] 2.782823

POINT( solution(V,5, 2,4), 5, "black")

# In this case (if we are able) we can solve the equation "by hand":

# (x-1/3)^2-1 = 5 I shift -1 to the right (subtraction -> addition)

# (x-1/3)^2 = 5+1 I make calculations

# (x-1/3)^2 = 6 The inverse of "^2" is the square root function

# x-1/3 = √6 I move -1/3 to the right

# x = √6+1/3 I make calculations (ie with computer)

# x = 2.782823

# If the solution of the equation corresponds to a point where the graph reaches a

# maximum or a minimum, as in the following case, the maxmin command seen above must

# be used to find the solution. Example: 28*x-99*x^2+14*x^3-49*x^4 = 2

# I look for x such that -28*x-99*x^2+14*x^3-49*x^4-2 = 0.

T = function(x) -28*x-99*x^2+14*x^3-49*x^4-2

graphF(T, -5,5, "blue")

graphF(T, -1,1, "blue")

# The graph does not climb over the x-axis. I cannot use "solution".

maxmin(T,-1,1)

# [1] 0.1428571

fraction( maxmin(T,-1,1) )

# [1] 1/7

T( 1/7 )

# [1] 1.94289e-16

# Because of the approximations, I do not obtain exactly 0.

POINT(1/7, 0, "red")

# Although we often consider functions that have as input and output individual numbers,

# in mathematics a FUNCTION is an outputs connection to inputs, where inputs/outputs

# can be of various kinds, even of a graphic type.

# Although we often consider functions that have as input and output individual numbers,

# in mathematics a FUNCTION is an outputs connection to inputs, where inputs/outputs

# can be of various kinds, even of a graphic type.

k = function(x) sort(x); a = c(5,2,1,3); k(a)

# 1 2 3 5

AND = function(x,y) x & y; AND(1>2, 1<3); AND(1<2, 1<3)

# FALSE TRUE

BF=2; HF=2; Plane(-2,2, -1,4); G = function(f,c) graph(f,-2,2,c)

f=function(x) x^2; G(f,"red"); g=function(x) x+1; G(g,"brown") |

|

STATISTICS

# (L) The first statistical calculations, which can be seen from the early years of

# school, are cross histograms. At a later time one can use the square or millimeter

# paper. Only then does it make sense to use the computer, to automate some of the

# process that we have learned to deal with "by hand". Here are some examples.

# The inhabitants (in thousands) of the North, the Center and the South (of Italy);

# the simplest way (bar, strip and pie chart):

N = 25755; C = 12068; S = 20843; Italia = c(N,C,S)

bar(Italia); pieC(Italia); strip(Italia)

# % 43.90107 20.57069 35.52824

# If I want, I can give names:

R = c("North","Center","South")

BarNames=R; bar(Italia); PieNames=R; pieC(Italia); StripNames=R; strip(Italia)

# % 43.90107 20.57069 35.52824

North Center South

# Or:

names = c("N","C","S")

BarNames = names; Bar(Italia)

PieNames = names; Pie(Italia)

Strip(Italia)

# yellow,cyan,... % 43.90107 20.57069 35.52824

# yellow,cyan,... N C S

# If I want, I can give names:

R = c("North","Center","South")

BarNames=R; bar(Italia); PieNames=R; pieC(Italia); StripNames=R; strip(Italia)

# % 43.90107 20.57069 35.52824

North Center South

# Or:

names = c("N","C","S")

BarNames = names; Bar(Italia)

PieNames = names; Pie(Italia)

Strip(Italia)

# yellow,cyan,... % 43.90107 20.57069 35.52824

# yellow,cyan,... N C S

# If I want I can use UNDER(name,x) and ABOVE(name,x) to put names under/above the

# bars; in x I must put the number of the bar. The same example (put 'UNDER("%",0.5)'

# if you want '%' under y-axis):

Bar( Italia ); ABOVE(Italia[1],1); ABOVE(Italia[2],2); ABOVE(Italia[3],3)

UNDER("North",1); UNDER("Center",2); UNDER("South",3); UNDER("%",0)

# If I want I can use UNDER(name,x) and ABOVE(name,x) to put names under/above the

# bars; in x I must put the number of the bar. The same example (put 'UNDER("%",0.5)'

# if you want '%' under y-axis):

Bar( Italia ); ABOVE(Italia[1],1); ABOVE(Italia[2],2); ABOVE(Italia[3],3)

UNDER("North",1); UNDER("Center",2); UNDER("South",3); UNDER("%",0)

# I can put names above/under the strip with above(name,x), under(name,x), under2(name,x)

Strip( Italia ); above("North",21); above("Center",53); above("South",82)

# I can put names above/under the strip with above(name,x), under(name,x), under2(name,x)

Strip( Italia ); above("North",21); above("Center",53); above("South",82)

Strip( Italia ); above(Italia[1],21); above(Italia[2],53); above(Italia[3],82)

under("Italy",25); under2("North-Center-South",25)

Strip( Italia ); above(Italia[1],21); above(Italia[2],53); above(Italia[3],82)

under("Italy",25); under2("North-Center-South",25)

# To get rounded percentage distribution - see (C) - I can do:

distribution(Italia, 0)

# 44 21 36

distribution(Italia, 2)

# 43.9 20.57 35.53 # if I want, then I write 43.90 instead of 43.9

distribution(Italia, -1)

# 40 20 40

# (M) These were already classified data. Let's see how to analyze individual data.

# As we see in the following example, we observe that commands can be broken over

# multiple rows. Here are the lengths of many broad beans (ie bean seeds) collected by

# a 12-year-old class. All lines must be copied and pasted, from "beans = c(" to the

# final line )".

beans = c(

1.35,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.50,1.65,1.90,

1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,2.25,

1.55,1.70,1.55,1.70,1.55,1.70,1.60,1.70,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.80,1.60,

1.80,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,1.00,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.30,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,

1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,

1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,

1.45,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.85,1.50,1.60,1.70,

1.85,1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.75,1.90,1.55,1.65,

1.75,1.95,1.55,1.65,1.75,2.00,1.55,1.65,1.75,2.30,1.35,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,

1.80,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.65,

1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,2.25,1.55,1.70,1.55,1.70,1.55,

1.70,1.60,1.70,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,

1.00,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.30,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,1.70,

1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,

1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.45,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,

1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.85,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.85,1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,

1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.75,1.90,1.55,1.65,1.75,1.95,1.55,1.65,1.75,

2.00,1.55,1.65,1.75,2.30

)

# We have already seen in (G) how to do some first analysis:

min(beans); max(beans); length(beans)

# 1 2.3 260

# A convenient way (it can also be made without a computer) to organize the data is

# the use of a kind of cross histogram, with the stem command. Example:

stem(beans)

# The decimal point is 1 digit(s) to the left of the |

# 10 | 00

# 11 |

# 12 |

# 13 | 0055

# 14 | 000000000000000000000055

# 15 | 0000000000000000000000005555555555555555

# 16 | 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000005555555555555555555555

# 17 | 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000005555555555555555555555

# 18 | 00000000000000000000000000000055555555

# 19 | 000000000000000055

# 20 | 00

# 21 |

# 22 | 55

# 23 | 00

# The first phrase ("The decimal …") says that the decimal point is a digit to the left

# of |, meaning that 10|00, 11|, … are for 1.0, 1.1,… Here's how I would represent the

# first six data of "beans" (1.35,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,1.80) on the squared paper. The

# computer sorts the digits to the right of | but it's not important to do so.

# To get rounded percentage distribution - see (C) - I can do:

distribution(Italia, 0)

# 44 21 36

distribution(Italia, 2)

# 43.9 20.57 35.53 # if I want, then I write 43.90 instead of 43.9

distribution(Italia, -1)

# 40 20 40

# (M) These were already classified data. Let's see how to analyze individual data.

# As we see in the following example, we observe that commands can be broken over

# multiple rows. Here are the lengths of many broad beans (ie bean seeds) collected by

# a 12-year-old class. All lines must be copied and pasted, from "beans = c(" to the

# final line )".

beans = c(

1.35,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.50,1.65,1.90,

1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,2.25,

1.55,1.70,1.55,1.70,1.55,1.70,1.60,1.70,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.80,1.60,

1.80,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,1.00,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.30,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,

1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,

1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,

1.45,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.85,1.50,1.60,1.70,

1.85,1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.75,1.90,1.55,1.65,

1.75,1.95,1.55,1.65,1.75,2.00,1.55,1.65,1.75,2.30,1.35,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,

1.80,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.40,1.65,1.85,1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.90,1.50,1.65,

1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,1.90,1.50,1.70,2.25,1.55,1.70,1.55,1.70,1.55,

1.70,1.60,1.70,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.75,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,1.60,1.80,

1.00,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.30,1.55,1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.75,1.40,1.60,1.70,

1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,

1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.40,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.45,1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,

1.60,1.70,1.80,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.85,1.50,1.60,1.70,1.85,1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,

1.50,1.60,1.75,1.90,1.50,1.65,1.75,1.90,1.55,1.65,1.75,1.95,1.55,1.65,1.75,

2.00,1.55,1.65,1.75,2.30

)

# We have already seen in (G) how to do some first analysis:

min(beans); max(beans); length(beans)

# 1 2.3 260

# A convenient way (it can also be made without a computer) to organize the data is

# the use of a kind of cross histogram, with the stem command. Example:

stem(beans)

# The decimal point is 1 digit(s) to the left of the |

# 10 | 00

# 11 |

# 12 |

# 13 | 0055

# 14 | 000000000000000000000055

# 15 | 0000000000000000000000005555555555555555

# 16 | 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000005555555555555555555555

# 17 | 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000005555555555555555555555

# 18 | 00000000000000000000000000000055555555

# 19 | 000000000000000055

# 20 | 00

# 21 |

# 22 | 55

# 23 | 00

# The first phrase ("The decimal …") says that the decimal point is a digit to the left

# of |, meaning that 10|00, 11|, … are for 1.0, 1.1,… Here's how I would represent the

# first six data of "beans" (1.35,1.65,1.80,1.40,1.65,1.80) on the squared paper. The

# computer sorts the digits to the right of | but it's not important to do so.

# The name "stem" comes from the fact that the data thus placed has the shape of leaves

# arranged along a stem. I can command that stem, putting a smaller or larger number

# (as below) of 1, classifies the data differently:

stem(beans, 1.5)

# 10 | 00

# 10 |

# 11 |

# 11 |

# 12 |

# 12 |

# 13 | 00

# 13 | 55

# 14 | 0000000000000000000000

# 14 | 55

# 15 | 000000000000000000000000

# 15 | 5555555555555555

# 16 | 000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

# 16 | 5555555555555555555555

# 17 | 000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

# 17 | 5555555555555555555555

# 18 | 000000000000000000000000000000

# 18 | 55555555

# 19 | 0000000000000000

# 19 | 55

# 20 | 00

# 20 |

# 21 |

# 21 |

# 22 |

# 22 | 55

# 23 | 00

# After learning how to do "by hand" simple histograms, you can use the software:

histo(beans)

# [the distance of the sides of the grid is 5 %]

# Frequencies and percentage freq.:

# 2, 0,0, 4, 24, 40, 64, 64, 38, 18, 2,0,4

# 0.77,0,0,1.54,9.23,15.38,24.62,24.62,14.62,6.92,0.77,0,1.54

# The name "stem" comes from the fact that the data thus placed has the shape of leaves

# arranged along a stem. I can command that stem, putting a smaller or larger number

# (as below) of 1, classifies the data differently:

stem(beans, 1.5)

# 10 | 00

# 10 |

# 11 |

# 11 |

# 12 |

# 12 |

# 13 | 00

# 13 | 55

# 14 | 0000000000000000000000

# 14 | 55

# 15 | 000000000000000000000000

# 15 | 5555555555555555

# 16 | 000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

# 16 | 5555555555555555555555

# 17 | 000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

# 17 | 5555555555555555555555

# 18 | 000000000000000000000000000000

# 18 | 55555555

# 19 | 0000000000000000

# 19 | 55

# 20 | 00

# 20 |

# 21 |

# 21 |

# 22 |

# 22 | 55

# 23 | 00

# After learning how to do "by hand" simple histograms, you can use the software:

histo(beans)

# [the distance of the sides of the grid is 5 %]

# Frequencies and percentage freq.:

# 2, 0,0, 4, 24, 40, 64, 64, 38, 18, 2,0,4

# 0.77,0,0,1.54,9.23,15.38,24.62,24.62,14.62,6.92,0.77,0,1.54

# See here if you want to get

# graphs like the one on the right |

|

# If you use:

histogram(beans)

# you also have the following sentence, of which we will then see the meaning:

# For other statistics use morestat() or statistics(…)

# If the classes are many you can get the histogram to the right, first putting:

noClass=1

# As a number indicating where the data are (more or less), I can use the median, which

# is the central value of the data; if the values are 5 I take the 3rd one. If data is

# an even quantity there are two values in the center; usually one takes the first of

# them. In our case:

Median(beans)

# [1] 1.65

# I could also find it by ordering the values - see (G) -, which are 260, and taking

# the 130th:

beans1 = sort(beans); beans1[130]

# [1] 1.65

# If data is an odd quantity median gives the mean of the two values in the center; it

# "can" be used (instead of Median), but it can be have a larger number of significant

# digits than data. See here for an alternative.

# I could also find it by ordering the values - see (G) -, which are 260, and taking

# the 130th:

beans1 = sort(beans); beans1[130]

# [1] 1.65

# Another used value is the mean, the sum of the data divided by their amount:

sum(beans)/length(beans)

# [1] 1.659231

# I can also get it with the command mean. I should then round off his value:

mean(beans); round( mean(beans),2 )

# [1] 1.659231

# [1] 1.66

# (N) The histo/histogram command automatically chooses the intervals where the data

# is classified. In this way it is easy to build histograms even in basic school.

# If I want, I can build the histogram by choosing the intervals. If I type:

Histo(beans, 1,2.4, 0.2) # for "beans" see (M)

# (H written in upper case) I obtain the histogram from 1 to 2.4 with 0.2 wide classes

# Frequencies and percentage freq.:

# 2, 4, 64, 128, 56, 2, 4

# 0.77,1.54,24.62,49.23,21.54,0.77,1.54

With:

Histogram(beans, 1,2.4, 0.2)

# as suggested by the "histogram" outputs, I also have:

# For other statistics use morestat() or statistics(…). Let's do it:

morestat() # or: statistics(beans)

# Frequencies and percentage freq.:

# 2, 4, 64, 128, 56, 2, 4

# 0.77,1.54,24.62,49.23,21.54,0.77,1.54

With:

Histogram(beans, 1,2.4, 0.2)

# as suggested by the "histogram" outputs, I also have:

# For other statistics use morestat() or statistics(…). Let's do it:

morestat() # or: statistics(beans)

#

# Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

# 1.000 1.550 1.650 1.659 1.750 2.300

# The brown dots are 5^ and 95^ percentiles

# The red dot is the mean

# If I write noMean=1; morestat() - or statistics(beans) - the mean is not shown:

#

# Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

# 1.000 1.550 1.650 1.659 1.750 2.300

# The brown dots are 5^ and 95^ percentiles

# The red dot is the mean

# If I write noMean=1; morestat() - or statistics(beans) - the mean is not shown:

# The outputs of this command are only available at the age of 12 or 13, but can be very

# useful to the teachers:

# minimun, 1^ quartile (demarcation between the first 25% of data and the next ones),

# median (or 2^ quartile or 50^ percentile), mean, 3^ quartile (or 75^ percentile),

# maximum.

# This diagram, that has the shape of a "box with whiskers", is called boxplot.

# If I want only the boxplot I can use (possibly with noMean=1) statistics(beans).

# [statistic(…) does not even print the values] In any case, it is better to use it

# (instead of morestat) if the data are (by nature) integers.

# Another command is boxPlot. With the command out we can exclude data that is distant