1*5 = 5 5*5 = 25 25*5 = 125 625*5 = 3125 3125*5 = 15625

Le catene di Sant'Antonio (chain letters)

[1] Questa lettera, del 1935, fa parte di una delle prime catene di Sant'Antonio (chain letters - lettere a catena - in inglese). Cercate di capire come funziona la catena e spiegate come mai viene prospettato proprio quel ricavo (e in quali ipotesi lo si ottiene).

– Within three days make five copies of this letter, leaving off the name and address at the top and adding your name and address at the bottom, and mail to five friends to whom you wish prosperity to come. – In omitting the top name, send that person ten cents (10c) wrapped in paper as a charity donation. In turn, as your name leaves the list you will receive – Now is this worth a dime to you? – Have the faith your friend had and the chain will not be broken |

Qualche nota sulle chain letters, estratta da WikiPedia:

A typical chain letter consists of a message that attempts to convince the recipient to make a number of copies of the letter and then pass them on to as many recipients as possible.

Common methods used in chain letters include emotionally manipulative stories, get-rich-quickly

pyramid schemes (schemi piramidali per diventare rapidamente ricchi), and the exploitation of superstition to threaten the recipient with bad luck or even physical violence or death if he or she "breaks the chain" and refuses to adhere to the conditions set out in the letter. Chain letters started as actual letters that one received in the mail. Today, chain letters are generally no longer actual letters; they are sent through email messages.

There are two main types of chain letters:

– Hoaxes - Hoaxes attempt to trick or defraud users. A hoax could be malicious, instructing users to delete a file necessary to the operating system by claiming it is a virus. It could also be a scam that convinces users to send money or personal information. Phishing attacks could fall into this.

– Urban legends - Urban legends are designed to be redistributed and usually warn users of a threat or claim to be notifying them of important or urgent information. Another common form are the emails that promise users monetary rewards for forwarding the message or suggest that they are signing something that will be submitted to a particular group. Urban legends usually have no negative effect aside from wasted time.

In Europe, in the United States, ... chain letters that request money or other items of value and promise a substantial return to the participants are considered a form of gambling and therefore illegal.

Vedi i commenti presenti in [2]. Ecco come affrontare il problema con R:

1

.Last.value*5

.Last.value*5

.Last.value*5

.Last.value*5

.Last.value*5

.Last.value*5

# 1 5 25 125 625 3125 15625

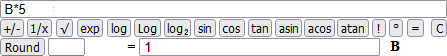

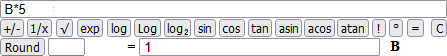

o con questa calcolatrice:

Nota. Le catene di Sant'Antonio sono nate più o meno quando si sono diffusi il moderno sistema postale e la capacità di leggere e scrivere, tra fine '800 e inizio '900. Le prime avevano forma di gioco: erano lettere della "buona fortuna" inviate a persone che a loro volta dovevano ciascuna inviarne copia a un dato numero di altre persone, con la promessa di una sorte favorevole per chi prosegue la catena e la minaccia di disgrazie per chi la interrompe. Successivamente, dopo la prima guerra mondiale, sono nate catene che prevedono l'invio di denaro, come quella dell'esercizio, e, poi, anche vere e proprie truffe: alla gente viene chiesto di investire risparmi nell'avvio di qualche attività economica o di diventare distributori di un certo prodotto e procacciare altri distributori. Con l'avvento della posta elettronica il fenomeno si è esteso, a livello sia di scherzo dannoso (messaggi che intasano le caselle di posta, che diffondono virus, …), sia di truffa (ora le leggi vietano sia le "catene di sant'Antonio" che possono creare danni, sia quelle attraverso cui vengono coinvolte le persone in imprese di tipo economico).

|

[2]

Non sappiamo se tutti proseguono la catena né quanti giorni impiegano a spedire le lettere e quanti queste ne impiegano ad arrivare. Supponiamo, per semplicità, che tutto

si svolga in modo uniforme e che passi esattamente una settimana tra l'arrivo della lettera

a una persona e l'arrivo di quelle che essa spedisce. Supponiamo, inoltre, che

ad ogni invio vengano contattate persone che non erano già state coinvolte

nella catena. Indichiamo con n il tempo

misurato in settimane da quando è stata inviata la prima lettera della catena e con

Quanto vale P(0)? Quanto vale P(1)? Quanto vale P(2)? Quanto vale P(5)? Il grafico a lato rappresenta Scegliete opportunamente la scala sull'asse verticale. Esprimete # Con R: P <- function(n) 5^n plot(P, 0,5, n=6, type="p") abline(v=axTicks(1), h=axTicks(2), col="blue",lty=3) plot(P, 0,5, n=6, add=TRUE, col="red", lty=2) P( c(0,1,2,3,4,5) )

|  |

Il numero delle persone coinvolte cresce vertiginosamente. La cosa

si vede anche sul grafico: la sua pendenza aumenta molto rapidamente,

tanto che, per riuscire a visualizzare

[3] Proviamo ad esplicitare la pendenza dei vari tratti del grafico. In tutti i tratti n varia di 1 (passa da 0 a 1, poi da 1 a 2, ...): Δn = 1.

| da 0 a 1: | P(0) = 1 | P(1) = 5 | ΔP = 5-1 = 4 | ΔP / Δn = 4/1 = 4 |

| da 1 a 2: | P(1) = 5 | P(2) = 52 | ΔP = 52-5 = 5(5-1) = 4·5 | ΔP / Δn = 4·5 |

| da 2 a 3: | P(2) = 52 | P(3) = 53 | ΔP = 53-52 = 4·52 | ΔP / Δn = 4·52 |

| da n a n+1: | P(n) = 5n | P(n+1) = 5n+1 | ΔP = 5n+1-5n = 4·5n | ΔP / Δn = 4·5n |

Ogni settimana

il numero delle persone a cui viene spedita la lettera è 5 volte quello delle

persone contattate la settimana precedente:

Una crescita di questo tipo viene chiamata esponenziale in quanto il valore